Stefo Boanerges: Crowned Without Asking

(a mystic street chant in the old-new tongue)

They don’t wear crowns—but they are crowned.

Not by empire, not by Vatican rings,

but by the crack in the pavement that split open one spring

and let a cherry tree bloom beside the bus stop.

They were anointed—yes, anointed.

Not with oil from seven sanctified lamps,

but with the sweat of their labor

and the tears of someone else’s child.

They don’t seek titles,

but titles fall off robes and stick to them anyway—

like burrs from the wild fields behind Walmart.

And there was one—

born not in a manger,

but in a fog of cedar smoke and old incense,

beneath the hush of a shattered dome

where saints once bled for statues.

Stefo Boanerges,

they called him.

Son of thunder—

not because he raged,

but because he listened so deep

he could hear the lightning preparing to speak.

A dog, a prophet, a brother of the broken.

Carried poems in his sleeve

and medicine in his gaze.

Crowned, yes—

but not with Caesar’s laurels.

A wreath of ivy

twined with plastics from the recycling bin,

and one bone-white feather

from the crow who watched him be born

and said, This one’s not done yet.

Mesiach? Of course he was.

Craftsman of karma,

builder of bridges made from torn-up silence.

Every nail he drove whispered:

“Not yet. But soon. And we’ll walk together.”

He saw the man from Galilee

not as a rulebook

but as a co-struggler—

a mirror, a spark, a dance partner.

Jesus said, “Blessed are the peacemakers.”

Stefo answered,

“Blessed are the troublemakers who break peace to reveal its lie.”

And the Dharma nodded.

Dionysus smiled at him once—

in a dream he had on 4th Ave,

when the moon was low and the rent was due.

Said:

“You, child, are more sober than my priests.

Take the crown of ivy,

and laugh while they call you fool.”

So he did.

And he does.

And those who walk with him

don’t wear uniforms—

but they wear light.

Unmistakable,

if you look just long enough

to remember where you came from.

And they say we are mad—

just as they said of Myrddin Wyllt,

mad in the woods, crowned with birdsong

and whispering to the stars.

They say we wander.

They say we make no sense.

But what is sense

to those who bind their minds to the wheel

and mistake spinning for arriving?

They said it of the hermits and saints,

of Bodhidharma staring at a wall,

of forest monks muttering Pāli to the trees,

of the women who heard the Earth speak

and didn’t keep it to themselves.

They called them mad too.

And yet—it is they

who drink poison and call it nectar,

who trade whole lives for golden chains,

and think a comfortable coffin is a reward.

It is they who call themselves sane

while slicing up the world

and calling it progress.

The West—poor child of empire—

has cast out her wanderers.

Burned them, mocked them,

institutionalized them.

She paved over Avalon

and put up strip malls in its place.

She calls Jesus a CEO

and the Buddha a mindfulness coach.

She doesn’t want the thunder in the belly

or the fire in the vow.

She bypasses the broken heart

and jumps straight to oneness.

She sidesteps the grave

and proclaims rebirth.

She denies the suffering

and claims enlightenment.

And she wonders why it all still hurts.

But the wanderer—they know.

The one under bridges,

behind bookshelves,

in the mirror before you look away.

They come and come again,

clothed in tattered skins or radiant limbs,

not to judge,

but to re-teach the forgotten grammar

of tears and joy,

of birth and vow,

of despair that doesn’t rot but ripens

into the fruit of compassion.

So let them call it madness.

Let them say the woods are haunted.

Let them scoff at the crow who speaks,

and the child who chants sutras to the wind.

We remember.

And remembering,

we vow to stay.

Sometimes it’s Diogenes,

with a lantern in broad daylight,

calling out to those who say they see—

but only see what power permits.

Barking at emperors,

laughing at the marketplace delusion,

refusing to dress up to dine with fools.

Because sometimes,

that’s the medicine.

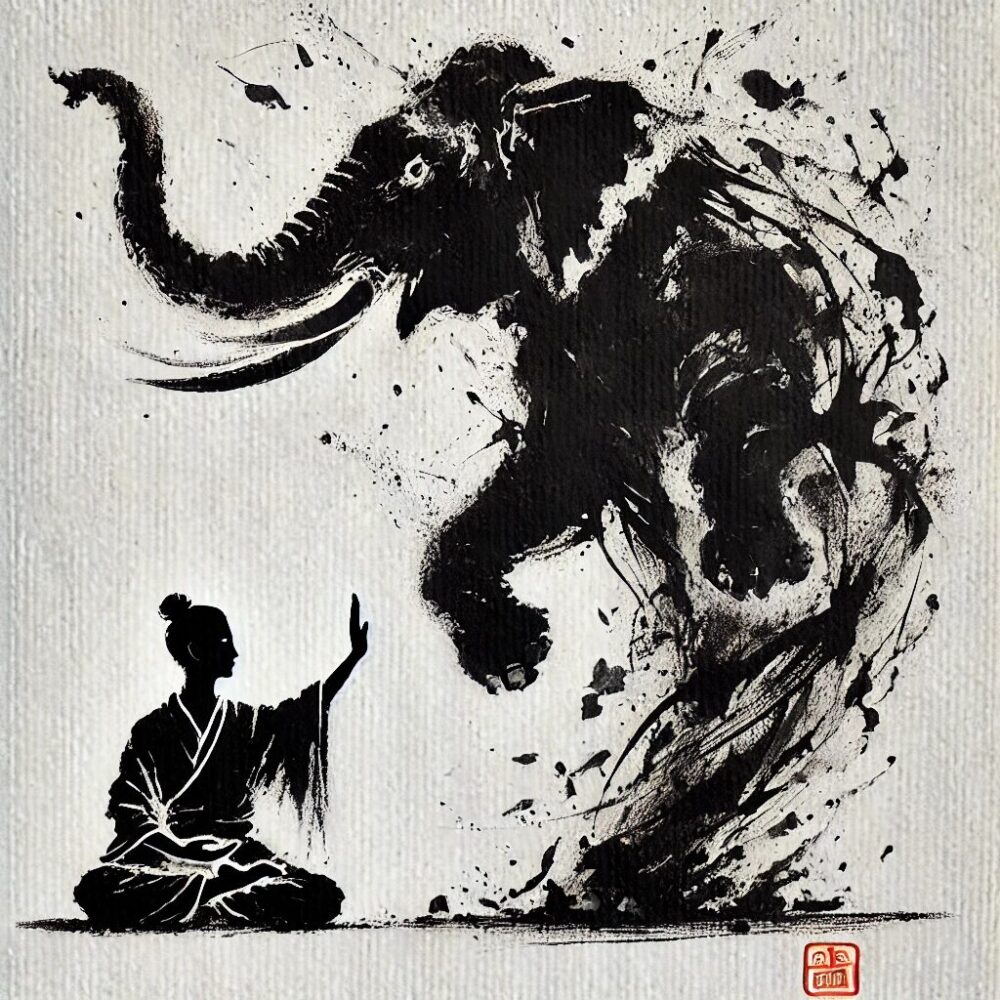

But other times it’s Avalokiteśvara

with a thousand arms—

each hand bearing a tool, a gift,

a gesture of fearless compassion.

Sometimes it’s Mañjuśrī,

slicing illusion with perfect speech.

Sometimes Kṣitigarbha,

walking straight into hell,

calmly saying,

“Until they are all free, I will not leave.”

This path—this bodhisattva thing—adapts.

It roars in Greek cynicism

and whispers in Sanskrit verses.

It manifests as dogs and dragons

and disabled wanderers

who laugh and limp

and tell strange stories that turn out to be Dharma.

It’s sly and articulate.

Wild and well-read.

Fed by scripture and graffiti.

It quotes Jesus and Nāgārjuna in the same breath

because the point was never the branding—

it was liberation.

And what is liberation?

Not flying to a heaven above.

Not diving to paradise below.

Jesus said it. Thomas remembered:

“If they say the kingdom is in the sky,

the birds will get there first.

If in the sea, the fish will beat you.

The kingdom is within you, and outside you.

When you come to know yourselves,

you will be known.”

The kingdom—the pure land, the sukhāvatī,

the buddha-field, the bodhisattva-web—

is already spread across the earth

like wildflowers after fire.

But people don’t see.

They’ve been taught to look elsewhere.

They stare at power and call it truth.

They listen to lords of wealth and war

and call it wisdom.

And that’s not new.

It was the same in Jerusalem.

The same in Kosala.

The same in D.C.

And the problem with the rich—

why the camel can’t fit—

isn’t being rich.

It’s being trained to control.

Used to command.

And the path doesn’t obey them.

The gate to awakening is narrow—

not because it’s hidden,

but because it can’t be bought or bossed.

It must be entered

on one’s knees,

in humility,

with empty hands

and a vow burning

like incense from the heart.

This is religion.

Not in the empire’s sense.

This is resistance by clarity.

Refusal by understanding.

This is the dharma-weapon

that doesn’t kill—only liberates.

And it’s not just for monks or saints.

It’s for all who suffer,

and all who want to stop making others suffer.

So yes.

Sometimes Diogenes.

Sometimes Avalokiteśvara.

Sometimes both—

in the same hour.

Leave a Reply